A while back, a Scientific American article described the work of the STRONG Kids Project, whose home is the Urbana-Champaign campus of the University of Illinois. The acronym stands for Synergistic Theory and Research on Obesity and Nutrition Group, and the piece contained one particular sentence so sadly appropriate today, and so likely to remain true for some time, that it may as well be carved in a medium only slightly less eternal than stone:

Parents, schools and even family doctors might be pardoned if they have neglected to consider some of the newly described factors that might be behind childhood obesity.

The newly described factors are so numerous! Even though we all hear plenty of news every day, it takes attention and effort for the baffling array of facts, suppositions, and promising hot discoveries to sink into our brains, and for us to catch up. Here’s the problem, as described by STRONG’s founder, Kristen Harrison, PhD:

It’s cellular makeup, it’s child behaviors and child attributes, it’s family behaviors within communities and environments within state and national level policies. It’s incredibly complex.

Add to those factors such random twists of fate as a child’s access to exercise and to stores with healthful food, how often a family eats dinner together, and so on. The researchers found what writer Rose Eveleth described as an “intricate web of forces” — complicated, interconnected and interacting with one another in unknown ways — that needed to be untangled.

To contemplate just one strand alone, for instance, proved to be far from simple, leading off into a number of different questions. The researchers looked at the information gathered by a group they had no connection with, whose interest was sleep.

They found that, contrary to their expectations, it was not the amount of sleep that mattered, it was timing, says Carol Maher, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of South Australia and lead researcher on the study. Children who went to bed early and got up early were far healthier than those who went to bed late and got up late, even though the two groups got the same amount of sleep.

It could be that those who go to sleep later spend more time watching television. Mornings tend to be better for exercise, whereas evenings are prime computer and television times — which means less exercise, more snacking, and more exposure to food marketing. But, Maher points out, it could also mean that kids who are more physically active during the day tend to get tired earlier, and go to bed earlier.

Is that complicated enough? And speaking of TV, the STRONG project found out that you can lump together gender, ethnicity, income and parental weight, and the cumulative burden of all those things will be a less accurate predictor of bad eating habits than the sole factor of television watching.

Next, Childhood Obesity News will look at what those dedicated and tenacious STRONG Kids Project team members have been up to in the meantime.

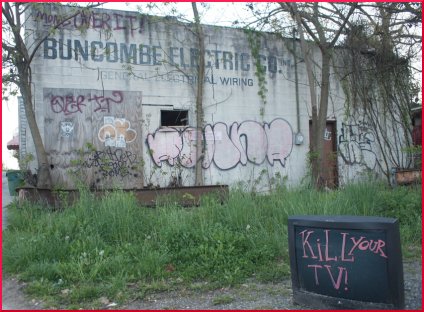

Picture Note: The photo on this page is by Anna Hanks, and the joke is that there once was a politician named Buncombe, whose name became synonymous with claptrap or nonsense, and eventually came to be spelled “bunkum,” meaning the same.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Hidden Drivers of Childhood Obesity Operate Behind the Scenes,” ScientificAmerican.com, 10/31/11

Image by anna Hanks

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: