Childhood Obesity News has been following along with advances in understanding the microbiome. The “connect the dots” trope is useful here. Seemingly, a whole constellation of dots are related in intriguing ways that don’t appear to add up to much—yet. Some dots to consider: obesity, diet, leaky gut syndrome, mental/emotional health, addiction, allergy, metabolic syndrome/diabetes, chronic inflammation, gestational influences, C-sections, antibiotics, artificial sweeteners, neurosteroids (the preferred term for hormones), and of course the various communities of bacteria in our digestive tracts.

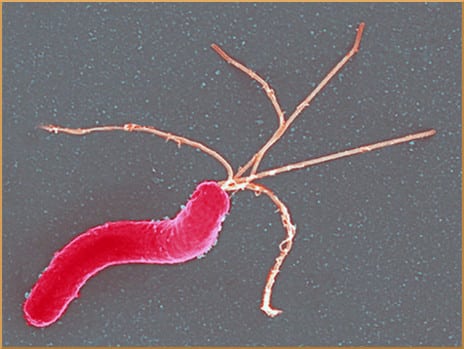

The microbiome appreciates balance and stability. Like any thriving ecosystem, it works on the principle, “A place for everything and everything in its place.” Although bacteria are quite adaptable, they do tend to specialize, and find a comfortable niche both geographically and functionally. To protect itself from the stomach’s acidic environment, Helicobacter pylori imitates a corkscrew and burrows into the stomach’s mucous lining. As Kenyon University’s MicrobeWiki describes it:

The motility of the bacteria, the flagella and the shape favors colonization which allows spiral shape to excavate through the lining.

This digging allows stomach acid flow to where it does not belong, and can cause gastritis, peptic ulcers, or gastric cancer, the currently recognized manifestations of H. pylori’s activities. Those holes created by the creatures also let large molecules into our bloodstream. This phenomenon is called leaky gut syndrome, and is associated with obesity.

H. pylori is able to turn a person’s body against itself, just like an autoimmune disease, and autoimmune disease is one of the “dots” that seem to want connection. Another connection is that a low-sugar diet concentrated on fruits and vegetables will reduce the H. pylori population—and will also reduce obesity.

Not content to merely hide from stomach acid, H. pylori produces chemicals that reduce the acidity. This may sound attractive at first blush, but stomach acid helps to keep down the populations of other kinds of destructive bacteria and parasites. Maybe we don’t want H. pylori to wage chemical warfare on its neighbors in our name, for its own competitive advantage.

H. Pylori’s Other Bad Habits

Apparently, H. pylori also steals manganese, which is definitely a hostile act, because our bodies need it for our own purposes. Manganese helps the body absorb other vitamins and metabolize cholesterol, carbohydrates, and glucose (obesity and diabetes connections). Ygoy Health Community says:

Due to antioxidant properties, this mineral can help you to control the flow of free radicals in human body. It is good news because these radicals are capable of damaging your cells…Manganese is a popular remedy for inflammation.

Inflammation is another obesity connection. Half of us are carrying around H. pylori and don’t even know it, because relatively few people get ulcers; those who do often lose weight, so how could anyone suspect H. pylori of being an obesity villain?

But the ways of microscopic creatures are subtle, and this bug is far from harmless. People who used to be overrun with H. pylori infection look back and share their experiences with brain fog, fatigue, allergies, and thyroid problems that are now cured. Coincidentally, the thyroid gland produces immensely influential neurosteroids that tell the whole body what to do, so there is another obesity connection.

H. pylori causes chronic low-level inflammation, and as we have seen, chronic inflammation is acknowledged to be associated with some citizens of the microbiome. Also, inflammation is a widely-observed link between obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and more recently, depression.

(To be continued…)

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Helicobacter pylori,” kenyon.edu, undated

Source: “Why Manganese is So Important,” ygoy,com, undated

Image by AJC

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: