Several international bodies combined their data and expertise to estimate the proportions of the obesity epidemic 15 years down the line. The “Background” and “Conclusion” sections of the report, published in September by the journal Pediatric Obesity, convey the gist:

Member states of the World Health Organization have adopted resolutions aiming to achieve “no increase on obesity levels” by 2025 (based on 2010 levels) for infants, adolescents and adults… The 2025 targets are unlikely to be met, and health service providers will need to plan for a significant increase in obesity-linked comorbidities.

The researchers were particularly interested to know what to expect in the way of co-morbidities, including hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance (which leads to metabolic syndrome), heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and fatty liver disease, as well as less threatening conditions that serve as precursors to co-morbidities. The report indicates that we should not be surprised if, by 2025, somewhere around 90 million of the world’s school-age children experience one or more of those problems.

Even five years ago, the increase in morbid obesity was noticed by pediatricians to a point that Dr. Pretlow called “alarming.” But why? He noted the tendency, in some quarters, to jump to a solution like bariatric surgery, and rhapsodize about what an acceptable safe effective treatment alternative it is, without ever examining the underlying reasons for the obesity.

Reasons for obesity

Probably the most frequent reason is addiction, an idea that has gained traction despite being hard to understand in some ways. Is it the food, or the overeating? Is it a substance addiction or a behavioral addiction? But like the “nature vs. nurture” debates that occupy sociologists, the precise roles played by the food itself and the individual’s psychology are difficult to pin down.

Undoubtedly, some foods taste better than others, and we have a very persuasive flavor receptor for “umami.” There is also no question that millions of dollars are poured into research to make foods irresistible. To the greatest possible extent, addictiveness is deliberately engineered.

On the other hand, an enormous amount of evidence points to the same kinds of emotional difficulties so often found in people who become addicted to substances. Links also exist with behavioral addictions like gambling, that have nothing to do with food. Tolerance is both a result and a cause of addictive behavior.

A large amount of anecdotal evidence suggests that individuals are different, and there may be a spectrum. Some people have a personal chemistry, quite possibly generated by the microbiome, that lends itself to cellular-level addiction. For others, the quality of the food is less important than other considerations, like availability and quantity.

Dr. Pretlow describes another kind of spectrum:

The observation that the children in this study struggled to lose weight proportional to their BMI percentile suggests that dependence on the pleasure of food may be on a continuum: overweight children may be only partially dependent (addicted); obese children may be fully dependent (addicted); and morbidly obese children may be in addictive tolerance mode. Thus, they eat larger amounts and higher pleasure-level foods to obtain the same degree of comfort.

Tolerance seems to be universally found in addiction, where escalation is the name of the game. On the most practical level, anything that can interrupt the seemingly inevitable march toward ever-increasing use of the addictor is a very useful intervention.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “Planning for the worst: estimates of obesity and comorbidities in school-age children in 2025,” Wiley.com, 09/29/16

Source: “Qualitative Internet Study,” tandfonline.com, 06/21/11

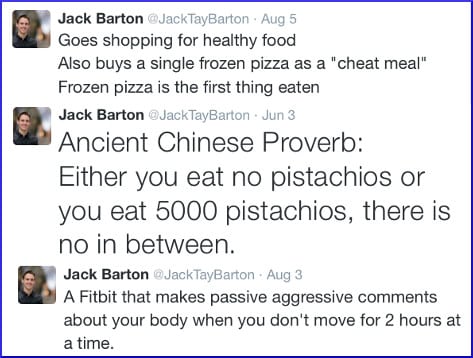

Image by @JackTayBarton

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests:

One Response