In the endeavor to reduce childhood obesity — at least far enough that it can no longer be considered an epidemic — long-term change is what one journalist called “the brass ring.” For readers unfamiliar with the concept, the brass ring is the prize that carousel riders try to reach as their horses circle around. Grabbing it entitles the person to a free ride. Actually, it’s not a very good analogy. What we want is for the child to get off the merry-go-round entirely, and out of the vicious cycle of loss and gain.

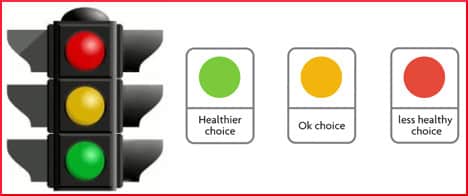

One way to do this, researchers have discovered, is to make the healthy food choice the easy food choice. The goal is to create a new, healthy habit of automatically making the best nutritional choice, and what could be more automatic than responding to a simple color-coding system?

Green is for the healthiest items, like vegetables and fruits and lean protein. Yellow means so-so, and red signifies that nutritional value is either minimal or nonexistent. The person doesn’t have to read the small print, and the basic message is discernible even to someone who can’t read. Traffic-light labeling makes life easier for parents and children alike.

Mixed results

However, the results seem to be mixed. Australia’s University of Newcastle did an experiment with families whose children were between 3 and 12 years old. It involved telephone interviews and questions about imaginary menus, and led to the impression that traffic-light labeling is not a strong enough strategy to counteract the “key drivers” that influence food choices. The study’s “Conclusion” said:

This study provided no evidence to suggest that energy labeling or single traffic light labeling alone were effective in reducing the energy of fast food items selected from hypothetical fast food menus for purchase…. Additional strategies are needed to encourage healthier fast food purchases.

At Massachusetts General Hospital, a couple of research projects have been conducted in the cafeteria since 2010, concerning mostly adult employees and visitors, but inevitably including some children and teens. Before traffic-light labels were overtly applied to food items, the cash registers were able to track all the food items and get a baseline reading. Then when a six-month period with visible labels was completed, information was compared, and it turned out labeling helped people make better choices. But was it just the novelty? Would the improving effect last over time? Or would “label fatigue” kick in, gradually inducing people to go back to their old, bad ways?

Dr. Anne Thorndike, of the hospital’s Division of General Medicine, wanted to know, so she designed another study which also included the tweaking of some locations. For instance, an effort was made to keep green-light items at eye level where they would be more easily encountered. This experiment lasted two years, tracking well over 6,000 transactions on an average day, and found that customers still paid attention even after the newness wore off. Journalist Mary MacVean wrote:

The researchers reported Tuesday in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine that sales of ‘red’ foods decreased from 24% of food sales at the start to 20% at two years; red beverages went from 26% of beverage sales to 17% at two years. Green foods sales grew from 41% to 46%, and green beverages from 52% to 60%.

The report gave credence to the idea that implementation of the traffic-light ratings would not decrease the food industry’s profits, which is a helpful thing to know if they are expected to support the program.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “The effect of energy and traffic light labelling on parent and child fast food selection: a randomised controlled trial,” ScienceDirect.com, 10/25/13

Source: “ ‘Traffic light’ food labels, positioning of healthy items produce lasting choice changes,” Eurekalert.org, 01/07/14

Source: “ ‘Traffic light’ food labels changed buying habits, study finds,” LATimes.com, 01/07/14

Image by World Packaging News

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: