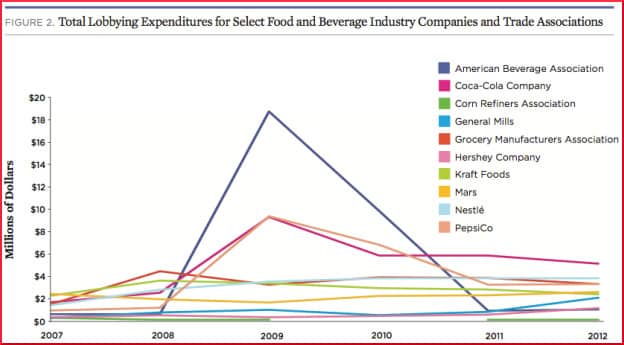

Whenever a threat to their continued profitability arises, the food and beverage industries react. The chart on this page was created by the Union of Concerned Scientists, and it’s the best kind of chart—one whose message can be read from across the room, one so blatantly, cartoonishly obvious it is almost comical. The huge increase in lobbyist spending in 2009, from under $2 million to almost $20 million in one year, was the result of a federal proposal to tax sugar-sweetened beverages. Rebecca Wilce wrote at that time:

According to the New England Journal of Medicine, 33 states already have sales tax on soft drinks, but the taxes (mean tax rate 5.2%) “are too small to affect consumption and the revenues are not earmarked for programs related to health.”

That is a problem, because earmarking for health-related problems is what leads people to vote in favor. The desire to impose what some call a “sin tax” is an effort to make the consumers of unhealthful food pay for the medical care they will eventually need. In this realm, SSBs are much easier to go after than solid food products. Liquids are sold in units that are uniform and amenable to measurement. Mainly, the task of definition is somewhat simplified because of the smaller range of possibilities and the relative ease of comparison.

Of course, there is still plenty of room for disagreement. For instance, industry lawyers can argue that orange juice, which is exempt from proposed taxes because of its health benefits, contains as much sugar per ounce as some soft drinks. Still, drawing guidelines for beverages is simpler than, for instance, ruling on an apple pie. Because apples are fruit, and fruit is good, and the government’s nutritional advisors want us to eat more fruit, right?

The Empire State Tries a Sin Tax

Michael Pollan once wrote:

It’s no accident that support for measures such as taxing soda is strongest in places like Massachusetts, where the solvency of the state and its insurance industry depends on figuring out how to reduce the rates of Type 2 diabetes and obesity.

With every passing year, more states feel the pain in their bank accounts, and awaken to awareness that today’s excesses are racking up major financial liabilities for the future. The industry tries to stay out in front the problem, seeking control and unwarranted influence by such means as preemption laws, which limit the ability of local governments to regulate restaurants. In Alabama, Arizona, Florida and Ohio, this was successful.

Early in 2010 the governor of New York State started to talk about taxing SSBs, and New York City’s formidable Mayor Bloomberg favored that goal, but state legislators voted it down. In the city he ran, Bloomberg tried to forbid the serving of soda portions larger than 16 ounces, but the soda business sued the city. In 2013 a judge ruled in favor of the business and against the attempted limitation. A gentleman named Michael Mudd, who had retired a decade earlier from an executive vice president post at Kraft Foods, became something of a whistleblower. Giving the public something to think about, the former industry bigwig wrote:

The executives who run these companies like to say they don’t create demand, they try only to satisfy it. “We’re just giving people what they want. We’re not putting a gun to their heads,” the refrain goes. Nothing could be further from the truth. Over the years, relentless efforts were made to increase the number of “eating occasions” people indulged in and the amount of food they consumed at each.

Bloomberg went on to use his money and influence in more easily persuadable places, and helped Mexico start taxing soda. In the spring of 2015 reporter Dan Goldberg wrote:

Some studies have found only a minimal impact, but a recent survey found a majority of Mexicans say they’re drinking less sugar this year and are also relating soda to health problems, after the country introduced a tax on sweet beverages.

But in the United States, a comparison was made between the annual per capita consumption of soda in 1998 (51 gallons) and in 2013 (44 gallons). Critics pointed out that this had been accomplished without an American soda tax, so why make a law when the desired good effect was already being accomplished through education?

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “ALEC and Coca-Cola: A “Classic” Collaboration,” PRWatch.org, 10/12/11

Source: “How Change Is Going to Come in the Food System,” TheNation.com, 09/14/11

Source: “How to Force Ethics on the Food Industry,” NYTimes.com, 03/16/13

Source: “Gillibrand disapproves of soda tax to fight obesity,” CapitalNewYork.com, 03/26/15

Image by Union of Concerned Scientists

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests:

One Response

Agreed that taxing soft drinks won’t change health behaviors whatsoever. As noted here, education is making a substantive difference with respect to encouraging a sensible diet and active life. Our member companies are also doing their part on this front – from offering a growing array of low- and no-calorie choices to advocating a better balance, via efforts such as national School Beverage Guidelines and the Balance Calories Initiative. Regulatory attempts have failed in the past, because they are arbitrary and unproductive. Let’s continue to have meaningful, education-based solutions instead.

-American Beverage Association