Last week, discussing a study performed at Washington University School of Medicine, Childhood Obesity News wondered whether a study with four sponsors, two of whom were Mondelez and Kraft, may not be totally reliable. To entertain suspicions about such research might be appropriate, because it would be greatly to the food industry’s advantage to show that they have no culpability in the childhood obesity epidemic. But that ship has already sailed—there is too much evidence, everywhere, to ever let the junk food corporations off the hook.

Last week, discussing a study performed at Washington University School of Medicine, Childhood Obesity News wondered whether a study with four sponsors, two of whom were Mondelez and Kraft, may not be totally reliable. To entertain suspicions about such research might be appropriate, because it would be greatly to the food industry’s advantage to show that they have no culpability in the childhood obesity epidemic. But that ship has already sailed—there is too much evidence, everywhere, to ever let the junk food corporations off the hook.

Another way in which that study might be problematic was pointed out by the researchers behind another study, this one undertaken at Louisiana State University. Its authors questioned the concept of using sterile mice (not reproductively sterile, but raised to have no native germs) as subjects, noting:

There are several characteristics of germ-free mice…that undermine their utility and physiologic relevance. For example, germ-free mice are well known to be smaller than conventional mice, with decreased cardiac output and notably underdeveloped immune systems.

While the germ-free state of lab animals is a separate question, the Louisiana work was undertaken based on a background statement that included these words:

The prevalence of mental illness, particularly depression and dementia, is increased by obesity.

Here, we test the hypothesis that obesity-associated changes in gut microbiota are intrinsically able to impair neurocognitive behavior in mice.

These researchers confirmed that the health of the central nervous system depends on a sturdy gut microbiome. When their demographics are imbalanced, the state of dysbiosis affects neural processes, immune activation, and inflammation—all of which play a role in disorders that span the territory between psychiatric and neurological.

When gut microbes are nourished by a high fat diet, they just might get rowdy and promote the increase of intestinal permeability, a.k.a. leaky gut syndrome, along with inflammation in every part of the body. The authors concluded that their data reinforced the link between gut dysbiois and neurologic malfunction, and suggested that dietary modification or drugs could improve the situation. Still, their acknowledgment and disclosure paragraph does not include any pharmaceutical company. It credits the National Institutes of Health, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, and Louisiana State University, with no indication of corporate support.

Stanford University research by microbiologist David Relman examined the role of the gut microbiome in balancing the hormones, such as leptin, that influence our feeding behavior. That work was sponsored by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Research in Canada

Another study with no apparent links to the food industry comes from the Department of Kinesiology at Laval University in Québec. Published by the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, it suggested that since the gut microbiome is associated with weight control and energy homeostasis, it must obviously play a role in obesity (or its absence).

These researchers were interested in the effectiveness of prebiotics and probiotics, both of which can change the populations of intestinal fauna. Probiotic medicines contain actual desirable bacteria, while prebiotics contain food that friendly bugs like to eat. The microbes, in turn, can affect appetite, eating habits, fat storage, and even metabolic functions, “through gastrointestinal pathways and modulation of the gut bacterial community.” The authors add:

The physiologic functions attributed to gut microbiota have extended to extraintestinal tissues, such as the liver, brain, and adipose tissue, constructing novel connections with obesity and related disorders including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease…Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota may lead to obesity via different mechanisms.

Although pre- and probiotics have been tested on adults in the effort to both prevent and treat obesity, this team expressed regret that relatively little work has been done with children, for whom a new dietary solution would be of enormous help. The report is admirably thorough, with 81 referential footnotes. The pertinent disclosure clause says, “There are no conflicts of interest to declare.”

Another Canadian study, this one originating at the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, also was interested in prebiotic fiber, because the intestinal inhabitants happily accept it and reward us by functioning brilliantly. That research was funded by a grant from the BMO Financial group, which has a lot to do with wealth management and investment banking, but is not a manufacturer of food, junky or otherwise. Dr. Raylene Reimer told the press:

With this award, our team will now be able to determine if (prebiotic fiber) can be applied to children and incorporated into the guidelines of pediatric obesity management.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “_Obese-type Gut Microbiota Induce Neurobehavioral Changes in the Absence of Obesity,” biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com, 04/01/15

Source: “Artificial Sweeteners May Change Our Gut Bacteria in Dangerous Ways,” ScientificAmerican.com, 03/17/15

Source: “Childhood Obesity: A Role for Gut Microbiota?,” MDPI.com, 2015

Source: “Why prebiotics could be key to fighting obesity,” GlobalNews.ca, 10/15/13

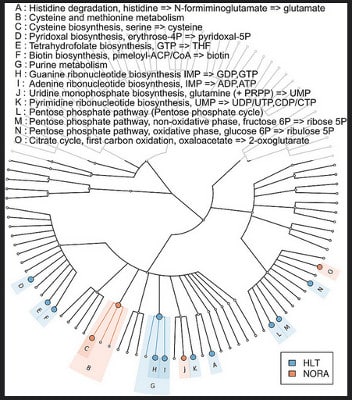

Image by eLife.01202.F8.large

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: