First let’s talk about the CEBQ, which we can do eloquently by borrowing the words of the Nathan Kline Institute, a.k.a. the Child Mind Institute:

The CEBQ is a 35-item informant-report questionnaire assessing eating style in children. Eating style is assessed on 8 scales (food responsiveness, enjoyment of food, emotional overeating, desire to drink, satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, emotional undereating, and fussiness). Informants rate the frequency of their child’s behaviors and experiences on a 5-point scale: 1-never, 2-rarely, 3-sometimes, 4-often, 5-always.

This self-assessment was designed for the parents or caregivers of children between six and 11. Previously, Childhood Obesity News discussed a University of Michigan study of verbal communications between children and parents, about food and eating. It all starts with the CEBQ (and another questionnaire) which was completed by the mothers.

One thing the study authors have realized, is that the family-meals philosophy is really swimming against the current in an obesogenic society inundated with opportunities to snack on energy-dense foods. Another is that parents find it very hard to resist the idea of giving out a snack to “tide a child over” until the next meal. These days, very few children work in fields or coal mines, and some adults wonder how kids who spend most of their time staring at screens manage to work up such gargantuan appetites.

It does not seem to matter what anybody thinks about the food-saturated environment that envelops so much of North America. All kinds of temptations are out there, and short of hiring three shifts of guards, parents are unable to do much about it.

Even parents who fully appreciate the importance of good nutrition are frustrated by the amount of time it takes to prepare meals. In theory, the upper middle class, replete with crock pots and microwave ovens, should find cooking from scratch easier. But everybody is having a hard time.

Kids and food preparation

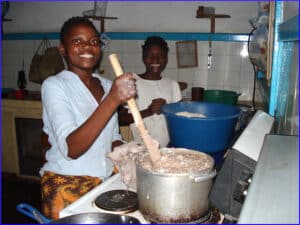

Before this study of the styles and modes of food talk, other researchers had found that a child who helps to prepare a meal is likely to eat more of it. The lesson parents can take from that is, if you’re going to cook at all, cook something worth eating. Sure, on very rare occasions, make s’mores together, or marshmallow rice squares. But if family cooking is a regular event, use the power for good, by cramming the menu with vegetables.

The University of Michigan study established that lots of food talk goes on during a family cooking session, which leads to the thought that it might be a good idea to purposely take advantage of those golden interludes. The time could be used to plan the next family cook-in, and a child could be in charge of making a nice decorated calendar page with a date commitment and a list of needed ingredients.

Even the dreaded electronic screen could be commandeered into use. Peeling and chopping vegetables can be boring, but the Internet provides innumerable videos about the history, uses, and nutritional values of foods, and listening together to experts can provide jumping-off points for all kinds of family discussions.

Your responses and feedback are welcome!

Source: “The Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire,” NITRC.org, undated

Source: “Family food talk, child eating behavior, and maternal feeding practices,” NIH.gov, 06/03/17

Photo credit: mozmamavicki on Visualhunt/CC BY-SA

FAQs and Media Requests:

FAQs and Media Requests: